At such a moment Man forgets himself and the God and, like a traitor, but in the way of holiness, he turns about. For at the furthest frontier of suffering nothing else stands but the condition of time and place.

— Hölderlin, Commentary on Sophocles’ Oedipus

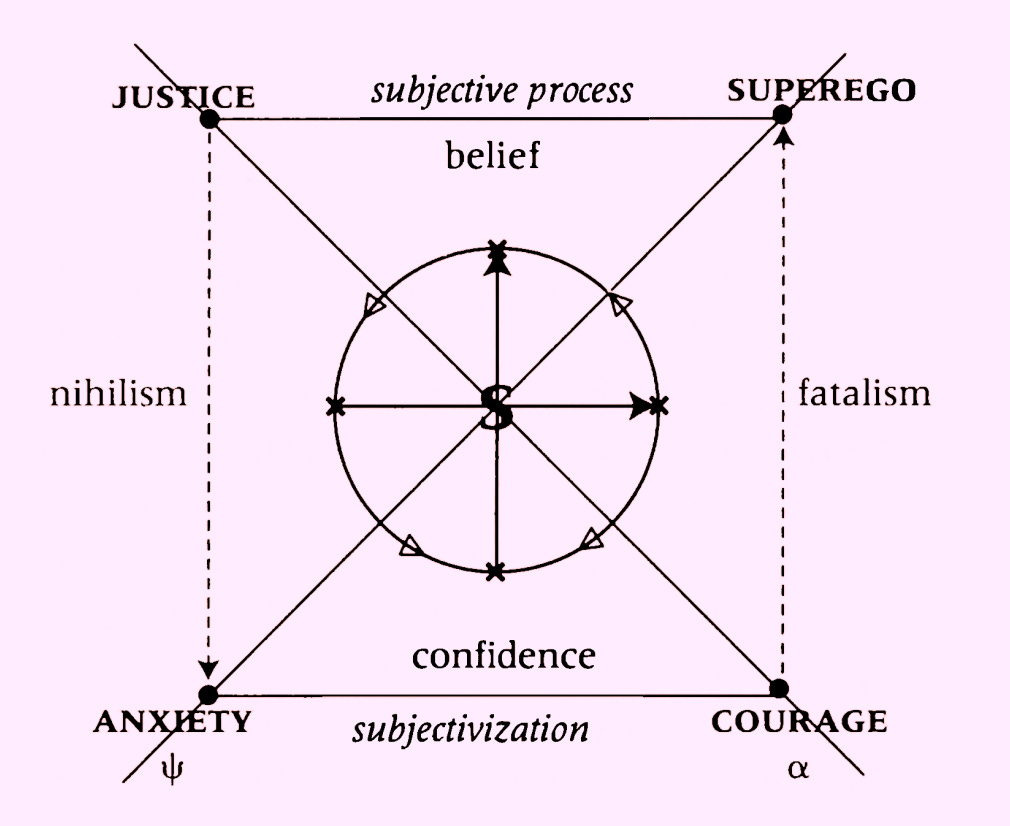

I believe that this subjective figure, whose dialectic is built on anxiety and the superego, always prevails in times of decadence and disarray, both in history and in life.

— Alain Badiou, Theory of the Subject

A few summers ago I read Stephen Crane’s classic American novel The Red Badge of Courage for a second time. The first time I read this novel it didn’t strike me as particularly noteworthy, and it certainly did not seem to elevate to a work that was communicating a profound philosophical message or series of themes. But I returned to this book after a surprising comment from my philosophical mentor Alain Badiou; he once wrote that it is the “best manual” for how courage produces the subject in his Theory of the Subject (1980). Badiou takes this even further and cites The Red Badge of Courage as one of the best examples of the theory of the event. This is high praise for such a seemingly modest and unambitious novel. It thus only made sense that I read the book again and in doing so I discovered what all the fuss is about.

In Badiou’s account, the novel not only describes what an event is, it offers up an account of courage that is distinctly Sophoclean. It is not common that we think of Sophocles as a figure of virtue ethics but Badiou cites Hölderlin’s short commentary on Oedipus and Antigone as opening an entirely new window into the importance of Sophocles. Similarly, in After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre juxtaposes Aristotelean to Sophoclean conceptions of the virtues in the following way. For Aristotle, courage is bound up with the Homeric conception of courage as a form of glory bestowed on the soldier who acts courageously for the sake of his household and his community.1 To act courageously is to bring a balance to the wider community and to affirm one’s place in the wider society. This is how we can understand Aristotle’s wider notion of the virtues, they are based on a balancing of the Golden Mean. In the case of courage, this balancing entails “observance of the mean with regard to things that excite confidence or fear.” Courage in battle is therefore grounded in the choice of the soldier to stick to his post because it is noble to do so. Importantly, through this character-based theory of virtue, the individual must possess a prior noble character before courage can come and this is why the objective is to hone one’s decision making to adhere to the Golden Mean and to repeat wise decisions. This is the way that character is built and why courage is to fundamental among all of the other virtues as “men are called courageous for enduring painful things.”2

In the Sophoclean account of the virtues, we find an entirely different account of courage that measures courage in distinct situations and moments that upend conventional time and place. In this account, courage occurs when the hero encounters a conflict that transcends their place in the community, i.e., virtues are developed in moments of action or in profound events that disrupt the status quo. Aristotle’s character-based account of the virtues is based on a stable and honed character development that occurs over the duration of one’s life and away from the scene of the action, whereas the Sophoclean character is flung into situations that uproot their stable relations, both of the self and of the self’s relations with the social community (the family, the city etc.) MacIntyre describes the ‘Sophoclean self’ as that figure that

[T]ranscends the limitations of social roles and is able to put those roles into question, but it remains accountable to the point of death and accountable precisely for the way in which it handles itself in those conflicts which make the heroic view no longer possible.3

Hölderlin’s brief and deeply dense account of Sophocles’s Antigone and Oedipus not only displays this notion that the hero becomes a figure that is cut off from social roles and convention, but this importantly opens a dimension of time that is empty, and infinitely divisible. The Sophoclean hero inhabits a time of eternity or Aion in the present—a time that is fundamentally atheistic, a time in which both man and god turn their backs on each other, leaving nothing by the “conditions of time and place.” Oedipus is the model of inhabiting of Aion as it is Oedipus’ drive to root out the atē or the hubristic drive i.e. Oedipus’ desire to not be determined by his fate drives him into a realm of the “unthinkable.” What Oedipus opens through his desire is akin to the Kantian transcendental:

Neither Fichte nor Hegel is the descendant of Kant—rather, it is Hölderlin, who discovers the emptiness of pure time and, in this emptiness, simultaneously the continued diversion of the divine, the prolonged fracture of the I and the constitutive passion of the self. Hölderlin saw in this form of time both the essence of tragedy and the adventure of Oedipus, as though these were complementary figures of the same death instinct. Is it possible that Kantian philosophy should thus be the heir of Oedipus?4

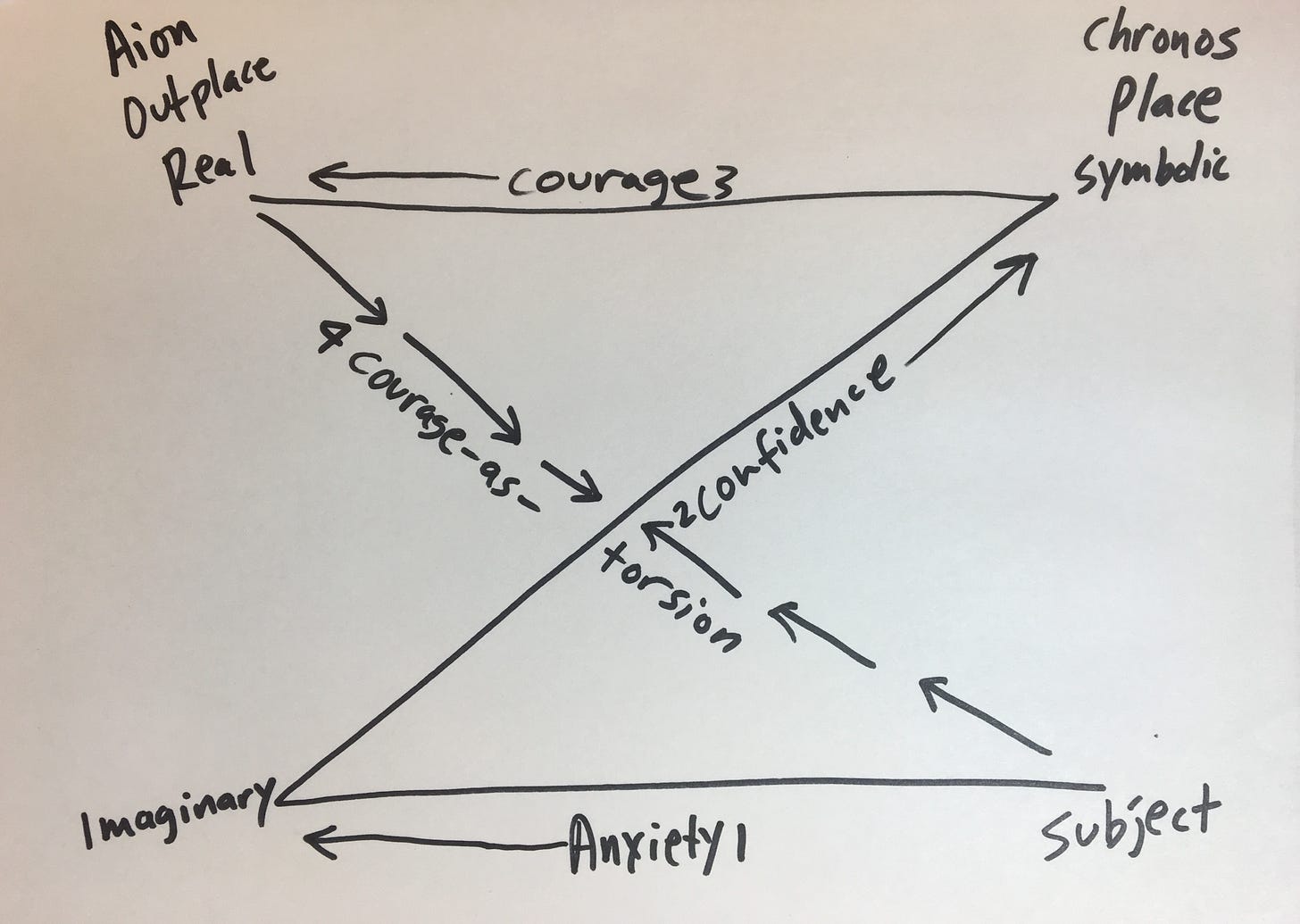

In his analysis of Antigone and Oedipus, Hölderlin demonstrates that anxiety is what displaces Oedipus and Antigone’s fixed roles and place in the social relations of the city and family. Anxiety is the primary affect in the movement of any subject out of their fixed place and time. Hölderlin thus conceives of the law as that force that places subjects in conformity to a symbolic logic situated in a fixed place—the scene of action in Sophocles’s tragedy’s is thus, as noted above, a three part situation: space, time and the hero’s actions. Anxiety is the primary affect because it challenges the fixed symbolic place as it works to deaden the law, anxiety interrupts the law with an excess of emotion that cannot be contained – a “too-muchness”5 that shakes the fixed law of the place. Anxiety, in its excessiveness, performs an operation on the law that exposes the law as a dead order of its symbolic injunctions. Anxiety reveals the law but only objectively as it presents “a question without and answer.”6 Anxiety sets free in the other side of the law — its rote and mechanical subordination to regimented chronos and segmented time and it also reveals the other side of the law as what Badiou refers to as the “nonlaw.” This is why anxiety is a “lamp bearer” of the truth of any given situation as the poet Stephane Mallarmé once wrote, it reveals the law of the place. Where anxiety exposes the split law, courage attempts a more radical displacement of the law by making a scission on the law in order to surpass it. Courage splits the law in two, revealing the law to be without assurance.

The Time and Place of Courage

The Four-Part Movement of The Red Badge of Courage

With this brief background in Sophoclean ethics, let us now examine the development of courage in Crane’s novel, looking specifically at how time and place shift registers as the action of the novel progresses. The actions of the battles occur in four sequences, each one shifting the protagonists’ relation to time and place. The action also seizes the protagonist with different affective states as he transitions his relation towards the battle throughout the novel. This affective dialectic presents the grounds for various cuts and breaks with one register of time and place to another. This affective dialectic will be developed in greater detail when we turn to Badiou’s ethics of action.

In what follows, I aim to elucidate the four movements of the novel with emphasis on how the youth enters into different temporal placements at each step. The first movement of the novel introduces the protagonist known anonymously as “The Youth” to the reader. The Youth finds himself trying to enter the assemblage of the battle unit. This initial movement into the battle is like a wild metonymic daze of anxiety, the Youth moves like a pinball searching for the hole; he bounces around the formation of the battle, too fearful to enter it. The Youth’s entry into the war strips him of his personal identity and prevents him from from being able to identify others in the army unit. He is unable to attach a cause to his overwhelming affect of anxiety, and his action remains aimless and metonymic.7

His failure to discover any mite of resemblance in their viewpoints made him more miserable than before. No one seemed to be wrestling with such a terrific personal problem. He was a mental outcast.8

The Youth’s anxiety propels him to confront the assemblage of the army unit itself and leave his personal comforts behind. Entering the battle means that “whatever he had learned of himself would be of little use” – the army assemblage becomes what Badiou names, apropos Mallarmé, the “lamp bearer” of the first movement in the dialectic. Badiou argues that anxiety is an affect that paradoxically carries with it a certain degree of light in that its function is to open the field up to its scissional opposite, namely courage.9 But before courage enters into the situation there must be a step out of anxiety and this requires confidence, i.e., it requires confidence to move from the metonymic pinball of anxiety towards courage.

At this early point in the novel, the Youth has attempted an anxious identification with the other soldiers as fellow nodes of anxiety and affect, but he winds up short, finding himself only faced with the hollowness of his own anxiety. No bond with the other soldiers can come about through anxiety alone. The Youth’s excessive anxiety must penetrate the assemblage of the army unit itself, a symbolic law that possesses what Badiou refers to as “iron laws of tradition and law on four sides.”10 Penetrating this symbolic complex of the assemblage is similar to entering the scene of the symbolic law itself – of entering the laws of the city as imposed by Creon in Sophocles’ Antigone. Overwhelmed with feeling completely isolated mentally, “he had feared that all of the untried men possessed a great and correct confidence”11 which he lacked.

He finally concluded that the only way to prove himself was to go into the blaze, and then figuratively to watch his legs to discover their merits and faults.12

To overcome his anxiety, the Youth realizes that he must master the laws of the army unit, i.e., he must enter the battle such that his movements and actions adhere to the rules of the unit itself. This crossing into the unit of the battalion is a disembodying phenomenon, it lifts the affect of anxiety and contorts his body to the instrumental rhythm of the unit itself. His experiment proved successful: “It was all plain that he had proceeded according to very correct and commendable rules. His actions had been sagacious things. They had been full of strategy. They were the work of master’s legs.”13 But this first brush with the assemblage proved overwhelming and he flees the battle retreating back into the quiet scene of nature, escaping the possible tragedy of getting wounded or killed.

In summary, the first dialectical movement is from anxiety into confidence, a movement that requires the decision of confidence to enter into the “iron laws” of the unit. Entering into the unit is a subjective process that propels the Youth into the temporality of the laws of the unit itself and these laws have a different temporality, namely, the time of the unit is chronos, a regimented, orderly time. Chronos is the time dictated by set intervals and increments. Whereas the battle appears from outside as pure chaos, inside the unity or assemblage, once the Youth enters it, the unit contains its own order of time, i.e., time adopts a law-like regimentation which takes over the body and determines the movements and actions of the bodies within it. Inside the assemblage unit, the Youth is completely subservient to the laws of the assemblage. This subservience eradicates the affect of anxiety because anxiety is an affect in search of an object and thus the subsumption into the assemblage nullifies this metonymic search.

What lies beyond the law of the unit is the attainment of courage itself. But in order to arrive at courage, the Youth must wager on an action that is beyond the law of the assemblage. The Youth must upset the laws of chronos within the assemblage, and in order to do so he must re-enter the assemblage. Here is how Crane describes the Youth’s reentry into the assemblage:

His mind flew in all directions. He conceived the two armies to be at each other panther fashion. He listened for a time. Then he began to run in the direction of the battle. He saw that it was an ironical thing for him to be running thus toward that which he had been at such pains to avoid. But he said, in substance, to himself that if the earth and the moon were about to clash, many persons would doubtless plan to get upon the roofs to witness the collision.14

This second reentry is now different, now the Youth enters the battle from a different temporal position. The narration of the novel also shifts perspective and the battle is told from a more detached and de-personalized position, i.e. the Youth enters the battle as if from the perspective of an impersonal global event—it is as if he is entering the battle as a spectator watching from a distant hillside preparing to get taken away in the chaos. The youth notes upon entering the battle this second time that “the noise was as the voice of an eloquent being, describing”15 — the battle is now experienced outside of the immediate time of anxiety— the time of chronos—or repetitive, linear time. The Youth enters the battle as a separate being now able to adapt to the laws of the assemblage more readily than before.

In his second touch with the unit the Youth is wounded in the battle, grazed by a bullet but it is not fatal. It is this wound that moves the Youth to an entirely new position around newfound courage. The third battle and movement of the novel opens with a return to the initial opening metonymic anxiety of his first movement but he now connects with a different form of identification.

All the roarders and lashers served to help him to magnify the dangers and horrors of the engagement that he might try to prove to himself that the thing with which men could charge him was in truth a symmetrical act. There was an amount of pleasure in watching the wild march of this vindication.16

There is now a marked difference in the Youth’s relation to the chaotic scene. He acts with total determination even gaining admiration from his comrades. “He had slept and, awakening, found himself a knight,”17 writes Crane. The perception of the youth is now more detached, as if he perceives the battle from a perspective that is outside of the assemblage and of chronos. “It appeared to the youth that he saw everything. Each blade of the green grass was bold and clear. He thought that he was aware of every change in the thin, transparent vapor that floated idly in the sheets.”18

The fourth and final battle now proceeds as if the eternal, cloudy perspective directs all subjective action. It is as if “the way seemed eternal” writes Crane and the affective weight of anxiety has been lifted – Fleming is actualized with a newfound relation to the action of the war. The novel ends with a glorious seizing of a hill where Fleming rushes to the top of the hill, raising the downed Union Army flag. Coming down from his victory, Crane writes, “it appeared as if the swift wings of their desires would have shattered against the iron gates of the impossible.”19 Fleming returned from this eternal place and “gradually his brain emerged from the clogged clouds, and at last he was enabled to more closely comprehend himself and circumstance.”20

The Importance of the Wound

Deleuze’s Ethics of Prudence

The pivotal moment in the novel occurs when the Youth receives the wound in the second battle, it is at this precise moment that the temporality shifts address and the Youth enters into the global event of the war. Upon attaining the wound, the battle hovers over its own field, but it is neutral to all of its actualizations, which is to say that the battle is only graspable by a new will that has been developed from the wound. It is the experience of the wound that splits open time from chronos to aion—it is the wound that brings the Youth into an eternal time.

let me briefly sketch the ethics the Deleuze develops in The Logic of Sense—my favorite book by Deleuze—to give you a better idea of how this Sophoclean ethics can look in practice. Deleuze reduces all ethical action to two subjective positions: revolutionary subjects capable of what he names ‘counter-actualization’ and those incapable of counter-actualization, or subjects caught within ressentiment. A subject of ressentiment is a subject unable to locate the pure event – subjects of ressentiment fail to will the event.

His notion of the event is metaphysical. It involves a Stoic concept of the body and it thus relies on a corporeal dimension of the event—each subject is responsible for their event, for living up to the dignity of their wounds. To adhere to the metaphysical dimension of the event is to enter into a type of becoming Deleuze names the “crack up.” The ethical task is to become like a crack-up, your task is not to shatter your body in the depths of a depression. This is why Lewis Carroll presents a version of becoming that is crazy, but not too much. He cracks up just enough at the surface, like a piece of fine porcelain with tiny little cracks that give the boy of the cup a certain dignity and refinement. Antonin Artaud, the avant garde playwright who Deleuze will later celebrate in Anti-Oedipus and Thousand Plateaus who provides the body without organs version of becoming is explicitly not the favored figure of ethical action. For the Deleuze of The Logic of Sense, the crack-up favors modesty and prudence in managing one’s situation; the task is to avoid the explosive power and drift into ressentiment.

Deleuze posits two forms of crack that the wound can take: there is the crack which extends its straight, incorporeal and silent line at the surface, and there is the crack from the wound that experiences external blows or noisy internal pressures which makes it deviate and deepen it in the body.21 These two options of the crack are indebted to the philosopher Maurice Blanchot’s distinction between personal death that is actualized in the harshest present and an impersonal death, which is not located in past or future. The difference between these two deaths resides in the figure of the “abstract thinker.” The abstract thinker is one version of the revolutionary subject who manages the prudence of the scission and crack. The question is one of becoming in light of the new knowledge of the surface that has been gained in the crack-up. Ethics is about managing the crack of the event that splits us as subjects? The question is not how do we become psychotic but how do we manage a moderate degree of craziness? Deleuze says that we should be careful to maintain the inherence of the incorporeal crack while taking care not to bring it into existence, and not to incarnate it in the depth of the body? This is the error that alcoholics make, and there are two kinds: there is the moderate alcoholic who incarnates the crack in the depths of their body (F. Scott Fitzgerald and the crack-up as porcelain) or the manic alcoholic whose excesses rise up into the manic heights (Malcolm Lowry and the alcoholism of the manic variety as depicted in his book Under the Volcano). Deleuze’s virtue ethics calls on the the subject to cultivate the virtue of prudence so as to manage the distribution of the crack and not fall into the schizophrenic depths or rise to the manic heights. Three levels: heights, surface and the depths. In some ways it is accurate to say that Deleuze incorporates both the Aristotelian attention to the moderate balance of either the heights or the depths — what matters is the surface. That is where true novelty happens. The Sophoclean ideas of scission and cut from ordinary time is an extremely powerful way to talk about a ethics of a situation, of a process-based ethics of events. The Nietzschean dimension to this ethical framework is built off a

A Marxist Ethics: From Sophocles to Aeschylus

Badiou also makes an attempt to generalize the Sophoclean framework of ethical action as early as his first major text Theory of the Subject (1980) but unlike Deleuze he does to in the direction of a Marxist ethics. In this text, Badiou talks about politics as a ‘place of force’ and ethics is about the management of the excessive core of the subject’s desire. He understands Marxist ethics to entail an inevitable breaking of the law. This means that the subject’s ethical actions have to think an insurrection from the law and the law refers both to the state and to desire. Badiou argues that the subject of courage passes through the superegoic injunction of the doubled law of the state and the superego and similar to the four-part movement we explored above. Badiou links courage to justice where the law is not only exceeded (courage) but then re-composed (justice). Antigone’s insistence on her brother’s burial is not merely an individualist demand bound up with her idiosyncratic desire; rather, her act of defiance reveals the brutal core of the state’s law and elevates this excessive law in such a way that it cannot be integrated back into the situation. In this model of ethical action, Badiou argues that anxiety is the affect that forces the law to a point where its excessive core is revealed. Courage is the affect that is required to bring this about, but the dialectic begins with anxiety and moves out of it into courage by first acting on confidence.22

The Sophoclean ethical paradigm posits that every social order contains a legal commandment and the obscene underside of this law is held in suspension within the law itself, what Badiou calls the “nonlaw.” As such, there is only an ethics-in-process, never an ethics of the whole, of a social being that is fixed in a determined place. In Antigone, we are presented with the nonlaw that serves as the dialectical opposite of the superegoic law of the state as embodied in Creon. Antigone’s insistence on her desire to bury her brother thus brings about the transparency of this doubled law of the state into visibility. But Badiou is critical of this paradigmatic example in that it does not provide the conditions for the subject to exceed force over the place.23 This inadequacy in the Sophoclean model of ethics leads Badiou to develop a theory of force or movement that is capable of going beyond death drive repetition, that displaces the law entirely. Anxiety is the name of the revealing of the doubleness of the law, courage is the testing of that law and justice is the re-composition of that law into something new. Badiou writes that “force is what, on the basis of the repeatable and dividing itself from the latter, comes into being as nonrepeatable.”24

In his move away from Sophocles’ death drive subject, Badiou poses a major break with the Lacanian and psychoanalytic notion of the subject. For Badiou, the subject is not defined in relation to a cause akin to that of the death drive, rather, the subject is defined by a shift, in which the ‘anxiety-superego’ axis of psychoanalysis is supplemented by the ‘courage-justice’ axis of revolutionary practice—this shift enables Badiou to conceptualize the consistency of the New against its re-inscription into the “old” symbolic order: the subject does not share with the psychoanalytical one the category of enjoyment, for the Event interrupts repetition, whose mechanism has no positive bearing on the force of this interruption and on subjectivization. Badiou finds his model of ethical action in another Greek tragedian, that of Aeschylus’ Oresteia specifically in the heroine Athena and Orestes. Unlike Oedipus and Antigone, Athena and Orestes do not “wander under the unthinkable” producing a unity of both superego (Creon) and anxiety (Antigone) that results in a bad infinity of interplays that provides no escape. Athena’s courageous refusal of Agamemnon’s demands are not devoured by anxiety and unlike Antigone, her subjective figure does not internalize the “debt of blood” with its endless allocations. Through courage and refusal Athena becomes the new subjective model for the name of justice. The Aeschylian option is superior for Badiou because it “interrupts the power of origin through the division of the One.”25 In the ethical figure of Orestes, the primary virtue that Badiou forms his ethics of the event around: namely that of fidelity to the event. For Orestes, following from the decision to insist on the courageous refusal of the law, a new infinity is opened up—an opening that must be organized as justice. As Badiou states, “this is what must be organized: that the infinite can proceed from an event that is real, and thus absurd from the point of view of the law.”26

Turning back to The Red Badge, let us analyze the event of the wound in Badiou’s framework now that we have developed some key contours of his system of ethics. The event of the novel is centered on the way the Youth transforms his actions in relation to the wound he receives in the second battle. The early Badiou of Theory of the Subject puts the term “virtue” together with other words referring to emotional experiences and phenomena; later work by Badiou refers to virtue by way of designating something separate from the affective. There are thus two forms of courage as a virtue in Badiou – the first affective and dialectical moving from anxiety to confidence, to courage and finally to justice. This other form of virtue as a concept and not an affect performs a radical operation on time. In a way this theory of time is similar to Deleuze’s radical subject that enters into a surface eternity of aion. Badiou’s subject of the event creates a new time that is subtracted from the prevailing temporalities of the default rhythms of life according to socio-historical business-as-usual and which is completely immeasurable according to the temporal-historical standards of established situations/worlds. As Badiou notes in his 2007 text Logics of Worlds,

We could also say that the event extracts from one time the possibility of another time. This other time, whose materiality envelops the consequences of the event, deserves the name of new present. The event is neither past nor future. It presents us with the present. Thus time does not do the splitting of anything; time is itself split by what is not being qua being. The subject keeps time and is unqualified.27

Time, for Badiou, is what makes way for the production of truths—because an event opens a new time, the discipline of the subject gathers and controls this new time. As A.J. Bartlett, Justin Clemens and Jon Roffe note, time is not a concept at all for Badiou but remains the ground of being, i.e. time is what gives being its strength, and it cannot be formalized.28 The subject is a friend or lover of time and works to construct a true present under conditions of an evental rupturing of time and place.

MacIntyre, Alasdair After Virtue University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana. Pgs. 151.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics trans. By F.H. Peters Barnes and Noble Inc., New York, NY, 2004. Pg. 58

MacIntyre, Alasdair After Virtue University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana. P. 143

Deleuze, Gilles Difference and Repetition trans. By Paul Patton, Columbia University Press, New York, NY, 1994. p. 87

Badiou, Alain Theory of the Subject translated by Bruno Bosteels, Continuum, New York NY, 2009. p. 291

Ibid, 292

Metonymic is a psychoanalytic concept that refers to the inability of a signifier to achieve full signification – a metonymic relation is one that is never at rest, one that never achieves full signification.

Crane, Stephen The Red Badge of Courage, D. Appleton and Co. New York, NY, 1990. p. 14

Here is how Badiou writes about this affective dialectic: “The first dialectical step consists in grasping the succession of two terms in strong difference from the vanishing of the causal term that articulates them, here the (setting) sun. If however the restricted night in which one operates is that of the empty salon is indivisible, this step is only a semblance. What matters is to salvage the trace of the day as internal scission of the nocturnal void. That is why anxiety is said to be a lamp bearer, carrier of light. This is not so much its reality as its duty. Its dialectical duty at which point the other side of the dialectic comes in and tolerates its scission: courage.” Badiou, Alain Theory of the Subject translated by Bruno Bosteels, Verso Books 2001, New York, NY. 107 – 108

Crane, Stephen The Red Badge of Courage, D. Appleton and Co. New York, NY, 1990. Pg. 16

Ibid, 8.

Ibid, 6.

Ibid, 33.

Ibid, 36.

Ibid, 36.

Ibid, 47.

Ibid, 73.

Ibid, 78.

Ibid, 194

Ibid, 98.

Ibid, 156

Badiou develops an ethics of confidence in Theory of the Subject and extends it to a Marxist ethics of proletarian subjectivity. In this ethics, the masses and the party form a dialectical relation to one another around a coming conception of justice.

Badiou, Theory of the Subject, Pg. 157

Ibid, 142

Ibid, 167

Badiou, Alain Ethics: An Essay in the Concept of Evil Verso Books, New York, NY 2007. Pg. 73

Badiou, Alain Logics of Worlds translated by Alberto Toscano, Continuum, New York, NY 2006. Pg. 90

Bartlett, A.J., Clemens, Justin and Roffe, Jon Lacan, Deleuze, Badiou Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, Scotland, 2014