Use Your Illusion

On the concept of the ego ideal for Christopher Lasch

You want to step into my world?

It’s a socio-psychotic state of bliss

You’ve been delayed in the real world

How many times have you hit and missed?

Guns N’ Roses, “My World” from Use Your Illusion II

The Relevance of Christopher Lasch’s Critique of the Left

Mention of Christopher Lasch’s critique of the left may very well be triggering to some. I remember participating in a panel on family abolition at the American Psychoanalytic Association (the first panel ever dedicated to this topic at the APA) and in my remarks I invoked Lasch’s critique of the family. My co-panelists later expressed a strong emotional response to my application of Lasch because they read Lasch as implicitly a ‘red-brown’ thinker. In other words, they read Lasch as Sophie Lewis suggests in her recent manifesto Abolish the Family, where she says that Lasch’s thought offers support to anti-feminist defenses of patriarchy.1 But Lewis then goes on to quote Nina Power and her work What Do Men Want as if Power is definitive proof that Lasch is destined to be co-opted by reactionaries.

Lasch’s critique of the left is not born from unfamiliarity with the radical left, and nor is it waged as a cheap rightwing opportunism. As I have argued in this interview, any assessment of Lasch has to begin with his writings in the 1950s which include his dissertation on American liberals reaction to Bolshevism and the events of 1917. He went on to pen a series of works that began Lasch’s odyssey in understanding the transformations on the American left in the mid-20th century, from Agony of the American Left, World of Nations and eventually to a polemical work called Haven in a Heartless World, a book on the family. All of these works must be assessed before anyone accuses Lasch of some sort of inevitable conservatism, they are each a relevant touchstone point for understanding a thinker who is best understood not as an enemy to the left, but as a deeply honest and critical interlocutor. With Barbara Ehrenreich and others, Lasch was a seminal figure in seeking to launch a socialist party in America, but this project fizzled out in the wake of the 1968 DNC Convention and a turn to a much darker and more nihilist sort of politics on the left.

After the tumultuous events of ‘68 and the chaotic state that the left found itself in, incapable of waging any serious electoral threat to the capitalist parties, and turning to an increasingly violent and subterranean politics, Lasch began a systematic Frankfurt School method of research. This began his mature period which consisted in a substantive critique of American culture which he came to be known by with The Culture of Narcissism. But importantly, as I mentioned, Lasch had already made his mark as a critic of the American left and even after ‘68, he remained a committed Marxist scholar. Lasch never renounces Marxism throughout this period all the while he is bringing a Freudian and Marxist critique of society to bear on the 1970s. As Gabriel Raeburn has noted in his incredible essay on the effort of Lasch and Eugene Genovese—a firebrand Marxist historian who unlike Lasch did became a conservative—to launch a Marxist academic journal called “Marxist Perspectives” in the 1970s; like the effort to start a socialist party, this project imploded due to infighting between the ideological rivalry that Lasch had with the New Left. Lasch’s more critical perspective itself cannot be pigeonholed as ‘Old Left’, because he certainly stakes out a number of critiques of that tendency in his early work.

The project to bring about a critical Marxist journal fell apart due to a single article that Lasch wrote on a critique of militant feminism entitled “Flight from Feelings.” As context, the counterculture had grown obscure and disconnected from mass politics, we had hyperbolic and over the top movements such as the SCUM Manifesto, just to give you a feel for the sort of feminist politics that were en vogue on the radical left at the time. Lasch’s article takes a polemical position on radical feminism, arguing that in practice much of it foments and accelerates divisions between the sexes, and that it moves away from a class analysis on the origins of resentments between men and women in the household.

At its core, Lasch’s “Flight from Feelings” article suggests that personal relations are becoming increasingly risky due to economic fragility, overwork and instability, but the effect of much of the discourse of radical feminism is to induce irrational rage and hatred across the sexes, especially when its demands placed on men and women alike are not met. Lasch argues that a lot of militant feminism is bound up with a progressive ideology that ends up making a virtue of emotional disengagement and this leads to the depersonalization of sex. He argues most directly—and controversially— that the new discourse on radical feminism does not permit women who may not subscribe to its doctrines, to “no longer be able to retreat to the safety of discredited conventions.” In other words, the radical left was shaping new norms of sex which were preventing the very sort of liberation they purported in a practice and lived manner, inside the household.

The article has a stinging polemical bite as polemical pieces do. It certainly provokes in the reader a sense that Lasch is not sensitive to the standpoint of feminist liberation, and in fact the article was so polemical that it caused a leadership crisis within the Marxist Perspectives journal which led to its eventual crash. Genovese loved the article and thought that Lasch should proceed with it regardless of the critics and it was that specific insistence by Genovese, a long-standing critic of the New Left and its turn to identity politics, that led to the collapse of the journal. But I read Lasch as more cooperative with the radical left than Genovese, and he was willing to revise the article to meet the expectations of dissenting feminist voices within the journal. But Genovese would have none of it and he ended up lashing out on Lasch, calling him a “coward.”2

The Ego Ideal: Ideology, Illusion & Desire

This background should give you a glimpse into the complexity that Lasch faced in his engagement with the radical left, an engagement that was deep and consistent over the entirety of his life. But I want to now turn to a particular conceptual approach that Lasch adopts in the Freudian field that I believe deeply informs his critique of the left as well as his immanent analysis of the crisis that faces the left in the post-68 milieu. Lasch is deeply influenced by the psychoanalyst Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel, a thinker who argued that the ‘ego ideal’ stands as one of Freud’s most important concepts. From her analysis of the ego ideal, Smirgel (along with Lasch) develop a particular understanding of the logic of narcissism in contemporary culture and based on this analysis, they understand the radical left, its demands and its conception of liberation based on the logic of the ego ideal.

Once we grasp the concept of the ego ideal we can begin to weigh its value and its strength as a concept for thinking politics and liberation. Freud first introduces the concept of the ego ideal in a 1914 essay, ‘On Narcissism’ where he defines it as an infantile illusion of omnipotence. In narcissism the subject identifies with the ego ideal, and Freud says that narcissism is not a perversion, but “the libidinal complement to the egoism of the instinct of self-preservation, a measure of which may justifiably be attributed to every creature.”3 The ego ideal is thus what Freud calls the target of the self-love which was enjoyed in childhood by the actual ego. The subject’s narcissism makes its appearance as a displacement on to a new ideal ego, which, like the infantile ego, finds itself possessed of every perfection that is of value.

Freud says that man is incapable of giving up a satisfaction he had once enjoyed, a truth of the libido, and thus man is not willing to forgo the narcissistic perfection of his childhood:

“[A]nd when, as he grows up, he is disturbed by the admonitions of others and by the awakening of his own critical judgement, so that he can no longer retain that perfection, he seeks to recover it in the new form of an ego ideal. What he projects before him as his ideal is the substitute for the lost narcissism of his childhood in which he was his own ideal.”4

The ego ideal is thus a constant and repeating source of nostalgia in our lives, it is an irrational desire for attaining an unobtainable lost perfection. At an early age, it governs the translation of our bodily needs into the register of desire. The ego ideal does not obey a death instinct according to Freud, it rather obeys a narcissistic impulse. And since we are unlike animals and do not have sexual periods where we are active and then inactive (our sexual impulse is constant) the sexual drive only heightens the narcissistic longing on which the ego ideal is based.

The ego ideal is irrational, it does not know death, it is bound up with the Nirvana Principle, and this principle is indifferent to bodily demands: it only seeks absolute release from tension. The only process by which the irrationality of the ego ideal can be mediated and thus brought under control is maturation and development, the process of overcoming paternal attachments (the Oedipus complex) thus comes to fundamentally butt heads with the ego ideal. The ego ideal is conditioned by social dynamics shaped by social norms and prohibitions.

In The Culture of Narcissism Lasch argues that American culture has depleted the ego ideal, and he diagnoses this as stemming from changes to the family, the rise of bureaucracy over everyday life, consumerism, the rise of therapeutic ideologies, and the attendant psychic woes this has brought about, from an increasing sense of hollowness in interior life, to the rise of authority that is often cruel, unhinged and imposing no limits. At issue for Lasch is a dialectic of the ego ideal with the process of maturation and working-through barriers; this has broken down in contemporary life, and this breakdown is encapsulated when Lasch says that the primary narcissism of the ‘imperial self’ is pushed into a dark empty corner because they lack the ego ideal.

An important point to note here is that the ego ideal is abandoned by Freud in 1924, as he turns to elaborate the death drive and the superego, the concept will take a backseat. But Lasch finds it a more dialectical concept than the death drive because it ties an account of subjective tension mediated with the social field, its logic is both internal and external. By dialectical we mean that the logic of the ego ideal and its irrationality must mediate, and thus compromise with the reality principle, it must interact with a process of overcoming the illusion of a pure blissful reunion; that is not going to occur in a non-antagonistic manner. This inevitably results in frustration and aggression. And in a society that no longer enforces maturation or possesses clear initiatory means by which subjects undergo a process of maturation, the ego ideal is embraced as irrational, and this only compounds a particular form of unmediated narcissism.

Importantly, the ego ideal has a personal narcissistic quality as it is located in unobtainable childhood illusions, the ego ideal marks us for life with this irrational desire born outside of limits. This is a lesson for aesthetics and artistic production as much as it is for politics given that the the artist is tapping into the same yearning as the political militant, both are aiming to recapture a fusion with a oneness to which they long ago displaced and substituted for other objects. We forget the ways that this displacement and substitution works but we should remember that it is a constant process, a life’s work that does not cease. This is the merit of the concept, it becomes a politico-ethical concept of the first order.

There is indeed an ethical task we must set on ourselves with knowledge into the ego ideal, namely, how do we avoid frustration and aggression that comes with the inevitable loss of omnipotence and wholeness? Politics, art and love are about the acceptance of limits, imperfection, flaws and lack. A politics that would refuse limits and imperfection is one bent on maintaining narcissistic illusions and this is what Smirgel refers to as “perversion.” Perversion is theorized as an attempt to overcome anxiety and the pain of separation by annulling any knowledge of the obstacles to the reunion of mother and child. Perversion denies the existence of obstacles and limits and the pervert refuses the procedures involved with maturing, which necessitate limits.

Freudian Marxism, particularly in the variants that follow Wilhelm Reich—according to Smirgel—only heightens a leftist desire which wants to preserve the infantile illusion of omnipotence. This has the practical effect of making the left advocate for an anti-social bond based in collective illusion, not based on leadership or limits. For Herbert Marcuse and Norman O Brown, two erstwhile and prominent Freudian-Marxists, the demands of politics revolves around the claim that civilization depends on regimentation and order it is not able to free eros. But Freudian-Marxism, precisely by conceiving of liberation in such a total way, as a freeing of all chains, only compounds the irrationality of the ego ideal which contributes to a loop of frustration on the left. In its aims to bring about a world where all needs are satisfied, where the world of harmony will finally reign, where contented humanity will dream no more, the left develops a social bond wherein each subject is promised a reunion with their ego ideal, but yet this illusion is one of personal omnipotence. When this illusion does not occur, as we experienced in 68, this results in persecution, censorship, scapegoating and an exaggerated blame game in which the left imbues a sense of omnipotence and exonerates itself as beyond critique. A new utopian socialism is formed in response to the failure of the left realizing its demands, the spirt of ‘68 wanes.

The Ego Ideal and Bourgeois Groups

Let’s carefully pick apart the merits of this critique of the left and the concept of a politics of illusion on which it is based. It is certainly useful to show how political ideologies, upon their failure or unrealizability activate aggressive censorship and even violence towards those who do not share that illusion. A community based on ideology—illusion is made synonymous with ideology for Smirgel and Lasch—has no dose of reality; they have organized around an individualist promise that mires each subject in primary narcissism, promising each member that they can find a solution to restoring their ego ideal.

I want to argue that ultimately, Smirgel and Lasch describe a condition of a group bond based in illusion that is confusing. Let me attempt now to provide a revamped application of their concept of the left by revisiting how Freud theorizes the bond of the revolutionary group in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego. For starters we have to understand that in the artificial group (church, army, corporation, as León Rozitchner suggests, we should refer to them as bourgeois groups) the social being of each member remains eternally in place; the function of the group is to serve as the subjective support for the invariable permanence of the system, institutions and power arrangements of bourgeois society. Thus, in the bourgeois group (synonymous with artificial group) each subject preserves an identical dependency that the self-enclosed adult maintains in the preservation of his or her infantile sensibility.

Artificial groups fall apart, they forfeit this bond that allows each subject access to their own ego ideal illusion. What happens when they fail to preserve relations in which each member can effectively satiate their ego ideals? This breakdown calls for a periodization into this very process, periods of stabilization are marked by bourgeois institutions stabilizing ego ideals and breakdowns are marked by inconsistency in this process. We are now at a more precise point to understand how the radical left enters the picture; I want to argue that the radical left emerges as a primary mediator of the breakdown in ego ideal dispensation within bourgeois groups and institutions.

What the post May 68 left points to is a grand counterrevolution in which a logic of revolt and rebellion is posed, an entire repertoire of demands aimed at a total obliteration of defective and repressive bourgeois ideals is waged, but the basis of this assault was absorbed by the bourgeois institutions. Counterculture leftist demands are, as Smirgel points out, fundamentally perverse in structure as they deny the existence of obstacles and limits. The pervert refuses castration and they form a rebellion based on the immediacy of demands for omnipotence and union with the ego ideal. What they thus fail to do is construct an ideal that would enable a different relay system from either the repressive bourgeois ideals or the return to the idiosyncratic narcissism of the ego ideals of each subject.

In this reading, post-68 leftism gave birth to a new solution to the narcissistic capitalist pursuit of personal ego ideals as it offered up a new conception of politics, one which now revolves around the claim that—as we see in Marcuse for example—if civilization depends on regimentation and order it is not able to free eros. A left that directs its activity towards the freeing of eros still of course leaves each rebellious subject in abeyance from any real achievement of pleasure because it has not offered a solution to the practical problem of limits, of initiation, of the reality principle itself. It promises only an ephemeral release, a temporary catharsis that will inevitably lead to a frustrated ludic politics, one that is ultimately still reliant on bourgeois institutions. We live in a time in which bourgeois institutions are capable of hollowing out their repressive ideals and swapping them in for newly enacted ludic ones, all the while maintaining relations of labor dependence on its subjects, this transvaluation, a classical left-Nietzschean counterrevolutionary gesture, is all the better for the maintenance of bourgeois groups.

What we are talking about is a new terrain, a new dialectic between the radical left and bourgeois groups, one in which the radical left compensates for the deficiencies of the bourgeois groups failure to mediate the ego ideals of its subjects. The argument that Lasch and Smirgel are making should thus be received by the left as a constructive criticism; it suggests that the left ends up filling in the lack of ideals within bourgeois group (this is a process that I refer to as “the paradox of liberation” in my book on the family.)5

The Left After the Breakdown of the Spirit of 68

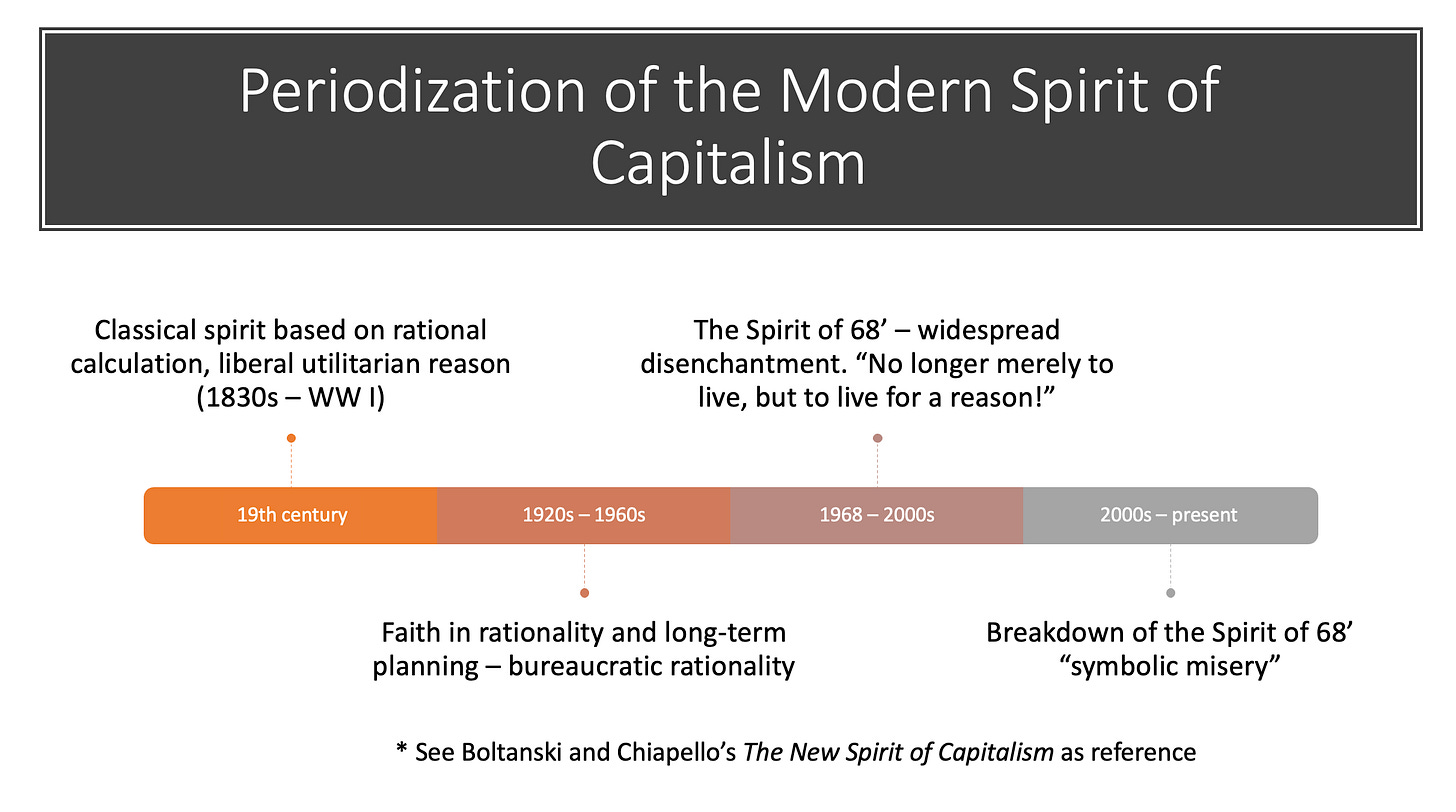

The premise of this dialectic between the left and bourgeois groups relies on a reading of The New Spirit of Capitalism, and we can periodize this system as follows:

We have to remember that the ego ideal is socially mediated; this is why the group is so essential in the maintenance of the ego ideal for the subject. There is a two-pronged struggle: subjects refuse socially imposed ego ideals, i.e., the normative imposition of ego ideals such as the market demands (austerity, frugality, competition for example) inevitably become the site of rivalry, in this reading the subject’s core aim is to recover lost satisfaction, and it will begrudgingly accept substitutions to this lost core. But there is nothing like touching the pure core of this lost satisfaction, there is nothing equivalent to the libidinal charge at stake in fulfilling what this reunification promises. And what it promises is a blissful submersion into the oneness of nature, into the oneness of the universe. And it is here that Lacan will enter the story with a radically alternative vision regarding this desire for a submersion into the blissful one.

It’s worth noting how different Lacan’s concept of narcissism is from this account. He maintains the stark opposite position to this claim; Lacan argues that blissful submersion into the motherly one only foments greater aggressivity in the subject. “The individual is most him or herself in the wondrous emptiness of being, rather than the personal Ego, the Other or the totality” as Raul Moncayo remarks in The Emptiness of Oedipus. I discuss this contrast between Lacan and Smirgel in a recent presentation with my study group on Lacan’s Seminar XVI “From an Other to the other.”

There are clear merits to Smirgel and Lasch’s claim that ideology can be understood via the ego ideal, i.e., as a promise or shelter for the restoration of the personal ego ideal as experienced in childhood. What this means is that ideology promises an all-too-easy reunification with personal ego ideals, and by this metric we can judge the effectiveness of an ideology based on the degree to which it satiates the longing for a return of its subjects to personal ego ideal identifications. The para-social dynamics on the left today, driven by online sub-communities are ultimately no longer about a mother fusion as its object as we witnessed in the spirit of 68 period, bourgeois institutions have placated and absorbed the ludic basis of leftist ideology to such an extent that we see emerge now a demand for communities organized around the demand for the father, wherein the goal of the leader is not to permit motherly bliss and reunion but to foster rational independence, responsibility, to accept limits.

See Lewis Sophie, Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation, Verso, 2022. p. 39.

With C. Derick Varn, I interviewed the historian Gabriel Raeburn on the rise and fall of Marxist Perspectives journal.

Freud, Sigmund “On Narcissism,” pp. 73 - 74

Ibid.

I define the paradox of liberation as “A dynamic facing liberatory movements when they must confront the collapse of the ego ideals and superego they revolted against and the concurrent challenge implicit in managing their own superego formation.”

Many thanks for this, Daniel. I found it a while back and was interested largely because I've been interested in Christopher Lasch's work for a while. Actually, I didn't know about his pre-Culture of Narcissism work, which was good to learn, and very useful. I reviewed a few books several years ago that referenced Lasch, and that's what got me more invested in his work. Reading this, and rereading the review I wrote, I was struck by how relevant everything you are saying is to the clinic today – I need to get this out there. Chapeau!