Marxism and Biography

In a time deprived of reality, biography should have a political application.

If all philosophy is biography, a statement Lou Salomé popularized in her book on Nietzsche, there is little to no agreement on whether biography matters for Marxism, or how Marxism is to think biography in its practice. There was an active debate about biography and Marxism accelerated by the rise of psychoanalysis and existentialism in the 20th century. Sartre famously accused Marxists of getting rid of the particular and of not ‘studying real men in depth.’ He argued that Marxism does not possess a theory of the concrete individual, and that Marxists, even so-called Marxist humanists dissolved real men in “a bath of sulphuric acid.” Sartre was driven to resolve this fundamental aporia at the heart of Marxism in his later years. Why else would he dedicate his final study to the most comprehensive philosophical biography ever written on Flaubert in The Family Idiot. But more on that later.1

If biography is to matter for Marxism biography must have a political valence. There is a tradition of Marxism, even in America, that sought to politicize biography. I’ve been enamored with this time during the Second International American left, back when they promoted proletarian realism. Importantly, realism is not equivalent to biography. Realism is a literary style and genre that places a subversive power over the personal, fictional and the memoir and all of these genres are bound up with biography, or at least they rely on a certain political understanding of biography. If done well, biography should be a catalyst for class consciousness.

There are many braindead ideas about realism in the wake of Cold War propaganda, and so it must be stated that realism does not avoid contradictions of everyday life; to the contrary, you could say realism in literature subverts the basis of what is taken for social reality. That is, good realism upends and reveals fetishisms over common reality. At stake in the question of how Marxism is to relate to biography is the way that biography can operate a political subversion on reality, and this means that instead of a conception of biography that would only draw out a great man theory of history or that would only insist on the biographical conceptions of the middle-class, we should investigate the meaning of proletarian biography in our time.

As a case study in biography and philosophy I would only draw on my own experience incorporating my biography in my book on Nietzsche, a thinker who fused his own biography with his philosophy. That I too, like him, decided to weave my biography into my book, especially my class experience, in a time of such profound middle-class ascendence, has elicited interesting responses. The general trend, anecdotally speaking, has been that many more senior scholars have seen my use of biography as a powerful testimony and as supportive of my argument. Some may think that we have an over-saturation of personal biography, and this might be evidenced by the rise of theory fiction, parasocial theory communities online, and even the increasing popularity in memoirs. But those arguments would have to acknowledge that we have an absence of discussion of class in personal biography, or put differently, to invoke class in your writing will scandalize the middle-class consensus. Appeals to class biography in writing has a profound liminal effect on readers. Such an approach to biography is transgressive because it goes against the post-class, middle class consensus. Biography should aim to elicit a political scandal in the reader.

Younger Nietzscheans have mostly been made uncomfortable by my biography and I interpret their uncomfort as bound up with my wider strategy to use my biography as a point of contrast to Nietzsche’s own highly class conscious approach to understanding biography and class being. Nietzsche did not shy from conceiving of his project in class terms and he continually attacked plebeian or lower class intellectuals, and thus biography, when wielded against that method is the root of my logic of a parasitical approach to Nietzsche. The aim is to upend the desired direction of his thought, which is to eradicate the lower class intellectual. If a reader has an awareness of this operation in Nietzsche it should be enough to mobilize him as an enemy, but that is not guaranteed, for the question of class is reverberated back onto the reader, which is why if one is not working class then that mobilizing effect may not materialize, or it may even be resisted or violently denied. Either way, Nietzsche is re-positioned as a pugilist in the context of his, and our present class struggles and we are invited to read him accordingly.

Materialism and Psychoanalysis

How can Marxism benefit from psychoanalysis in arriving at a materialist understanding of biography? We should begin by acknowledging that psychoanalysis promotes a primacy of internal factors over social and material factors in its understanding of the constitution of psychical structure and psychic mechanisms. But at the same time, Freud is not easily classifiable as an idealist if by that term we mean a system of thought that rejects social determination. And in order to complicate the primacy of internal mechanisms over their relation to the social system that is an embedded feature of psychoanalysis, a healthy materialist interpretation of psychoanalysis is both possible and necessary.

While it is a struggle to reach a materialist view on psychoanalysis, a careful analysis of Freud’s social and group psychology writings, as I have argued, do provide ample sources for a materialist reading and interpretation. Regardless, and to repeat, we have to understand (especially those of us who are sympathetic to Freudian-Marxism) that psychoanalysis is more prone to idealist frameworks than materialist frameworks. And moreover, the very tension of idealist and materialist applications of psychoanalysis should be made a central concern in any effort to bridge Freud with Marx.

This is a lesson that the tradition of Marxist or “critical psychology”—initiated by German psychologist Klaus Holzkamp—has argued for quite well. Holzkamp’s argument has direct bearing on biography because he claims that the individual in bourgeois society is thought in psychoanalysis in such a way that

“psychologizes societal class antagonisms as an expression of collective neuroticism — and it has always done this wherever it has dealt with such problems, beginning with Freud’s idea that in the October Revolution the “instinctual restrictions necessitated by society” and the aggressive tendencies arising from them were redirected outward as hostility of the poor against the rich, of the formerly powerless against the earlier holders of power.”2

Psychoanalysis thus reduces the individual not only to the primacy of internal mechanisms but it also, when read from a liberal political worldview, contributes to anti-politics.

For the American Freudian liberal critic Philip Rieff, anti-politics and the primacy of internal factors are to be understood as a great strength of psychoanalysis. For Rieff, as I have argued in my review essay on Freud: The Mind of the Moralist, psychoanalysis fosters an ‘anti-politics’ which means that it disables all rivaling ideologies, from religion to Marxism. Psychoanalysis is a class instrument for preserving the continuation of bourgeois culture because it offers up a theory of the individual which allows that individual to be understood as free from class determination or conflict. For Rieff, psychoanalysis neutralizes politics and it entirely supplants religion because it reveals that religious needs are ultimately psychological needs; if the conceptual armature of psychoanalysis can show that God the father is merely an affective identification rooted in psychic illusion and collective neurosis, psychoanalysis will have only triumphed over religion and Marxism. If Freud can prove that aggression describes the categories of evil and sin as projections that are ultimately reflections of deeper psychic complexes or perversions, this affects the metaphysical tradition of theodicy and hence psychoanalysis offers up a new morality.

Rieff is savvy enough to realize that the bourgeoisie or the middle-class relies on the end of ideologies or on the nominalization of all rival or competing ideologies in order to maintain its hegemony, and psychoanalysis, precisely by disabling the social and material basis of conflict, helps to pacify the class struggle. Psychoanalysis is thus an instrument of bourgeois class rule. Rieff, in classic liberal Nietzschean form, will suggest that Freud offers a morality for the bourgeoisie, a morality that, if applied properly, can shut down class struggle politics. Psychoanalysis is hence an updated “anti-politics”, updated from Nietzsche and his esoteric anti-politics, a topic that I address throughout my book.

Biography and Use-Time

With these provisos in mind, we need to ask how we might develop a conception of the individual that exceeds these pacifying logics of bourgeois anti-politics and the primacy of internal mechanisms, to the neglect of the social. The answer to this question returns us to the need to bridge Freud with Marx and therefore to do so will allow us a better understanding of how to contend with biography. At stake in the question of Marxism and biography is the need to develop a theory of the subject, or perhaps better ‘the personality’ that is not reductive to the primacy of internal mechanisms, but nor overly determined by external social factors. The thinker who has arguably gone the farthest in the domain of Marxism and biography is Lucien Sève, the French communist philosopher. In Sève’s work Marxism and the Theory of Human Personality and other works, he argues that Marxism lacks a theory of personality consistent with historical materialism.

“Psychology should not and indeed cannot be based on static concepts such as need, instinct, or desire because these things evolve with history and production, which is where the Marxist theory of the personality should begin: with development and change.”

Sève held that individuals’ personalities cannot, on the whole, go beyond the limits characteristic of their class or of the general degree of historical development of productive forces. This means that social institutions are understood to be appropriated by and determining of the life processes of individuals. And Sève, unlike many psychoanalytic accounts, argues that when considering biography, we have to emphasize that working-class people have in their biographies a high proportion of what he calls “abstract activity,” or activity aimed at creating profit and accumulating capital rather than fulfilling the workers’ needs. He opposes abstract activity to “concrete activity,” which entails learning new capacities that enhance the personality. Abstract and concrete activity are categories taken from Marx’s Capital in the field of labor and transposed onto the development of the personality. Personalities develop when their capacities increase, and Sève speaks of the “development of the fixed capital of the personality” and how for workers, there is a “bestial” mode of social existence, as Marx suggests in the Paris Manuscripts. Workers are impaired by the fact of labor demands and the robbing of personal time, but how does this reality actually shape the subject? This is what has to be theorized at the core of any biographical account.

In this way, as Julian Roche has shown in their study of Sève,3 human activity is shaped by time-dependence and Sève furthermore develops a helpful distinction between “use-time”, or the acts which constitute what Sève calls “the real infrastructure of the developed personality” with “abstract-time” or the time of capital and labor, i.e., stolen time. He places critical importance on use-time and he sees it as the fundamental quality that shapes personality, those with a high composition of abstract activity will become more alienated personalities (alienated in fact). Time is therefore what structures the field across which individuals’ activities unfold within their social relations, and this is the scene on which we must analyze a person’s biography. What is your structure of use-time, how does it unfold? This will mark the fundamental law of development of the personality according to Sève.

Sève’s concept of use-time helps us to understand a qualitative development of the personality in relation to the division of labor. If free time from labor constraints molds the development of the personality, biography must pay particular attention to work and leisure, to the balance of those with domestic duties and interpersonal relations. A focus on use-time allows us to see how the class and social being that determines middle-class subject, it is a promise that, crucially, does not consistently or reliably deliver for its middle class subjects, namely not everyone will use their use-time to become a cultivated individual. In fact, the dialectic of use-time and abstract-time is a site of contradictions where overlapping zones of life and self-becoming influenced by both labor and exemption from it interact and shape the individual. This dialectic is a way to track the development of capacities and alienation alike.

And this is why biographies of bourgeois failures who inhabit use-time in highly creative ways are of great interest. Flaubert and Proust are, by bourgeois standards, ‘failsons.’ Neither of them fulfilled their expected occupations and yet they both nonetheless reveal the necessity of use-time for inhabiting what Sartre calls ‘the imaginary.’ As Sartre shows in his study of Flaubert, his epileptic seizure occurred at the precise moment in which he was forced to leave his life of writerly seclusion to fulfill his parents demands that he become a doctor. In Sartre’s view, Flaubert’s seizure was a willed event, it was a strategy to remain holed up as a writer despite his parents demands. The seizure was thus not purely organic and as a strategy it worked. The seizure allowed Flaubert to remain in the use-time of a writer and once his father dies shortly after that, Flaubert goes on to fully inhabit this space thanks to his inheritance.

This interpretation of Flaubert’s seizure as a willed event in response to the loss of use-time is a good example of how Sartre will weave the psychoanalytic with the Marxist approach in his study of Flaubert. He reaches his highest point in this study when he suggests the concept of “misprison” or the notion that the collective worldview of a class, or a generation is not capable to cohere or remain in continuity with past classes or generations in history.4 This is why Flaubert practices a form of “black humanism” in which his vision of the social good is not formed in relation to the ideals of the liberal tradition that made his class possible, but are now, amid the crisis and revolution facing the possible dissolution of his class, causing him to retreat from any collective social commitment. This same sense of retreat from social engagement comes to define a certain type of realism that is also present in Balzac, as Adorno notes:

“Balzac attacks the world all the more the farther he moves away from it by creating it. There is an anecdote according to which Balzac turned his back on the political events of the March Revolution [of 1848] and went to his desk, saying, “Let’s get back to reality”; this anecdote describes him faithfully.”5

This observation should dispel any naive notion that realism is itself non-contradictory. If anything, what Balzac and Flaubert show is that realism is only possible by virtue of realizing use-time and it is the rarity of use-time, or otium,6 that stands as the great scandal of realism, allowing the authors a perch onto the present in a way that freezes the true exploitation and misery of the present. That realism is only accessible via the imaginary and the imaginary is conditioned on the writers removal from social life—the cocoon of use-time—indicates a highly political conception of Sartre’s imaginary. If revolution, for Balzac, only disrupts this cocoon, that is because revolution upends the perspective that the use-time has afforded the writer to truly see the core of society. Society is not observable without use-time. The author or the intellectual, more generally, dispenses a truth about this reality, but crucially, their labor is conditioned on it. The intellectual thus points to an inevitable scandal of time, however much they receive use-time it will come at a cost of a great scandal, of a great disorder in the division of labor, even for the bourgeoisie.

The Owl of Biography: ‘Objective Neurosis of the Age’

Sartre will argue that Flaubert’s work allowed him to pinpoint an “objective neurosis of the age,” that is, by weaving together the inner mechanism with the social conditions of Flaubert’s personal familial dramas Sartre identified a harmony between the two registers and thus pinpointed an 'objective neurosis of the age.' Flaubert’s neurosis is formed in a dialectic between both registers of the familial and the social and therefore a task of Marxist biography is to penetrate into this dialectic in any biographical study, so as to contribute to the knowability of social reality. In this sense, we return biography to the wider field of political epistemology, and thus to shaping a direction for engaging reality differently than anti-politics would suggest.

At stake in biography is the knowledge of the production of subjectivity with a focus on two dialectics: that of abstract-time and use-time, and that between the familial and the social as distinct zones of determination that interact. These two domains of biography allow us to develop a measure for gauging the unfulfilled project of the subject, for seeing at the same time the desire and hence the struggle of becoming in relation to these processes. As a wager for more study in the future, the question of proletarian biography should be propagated today.

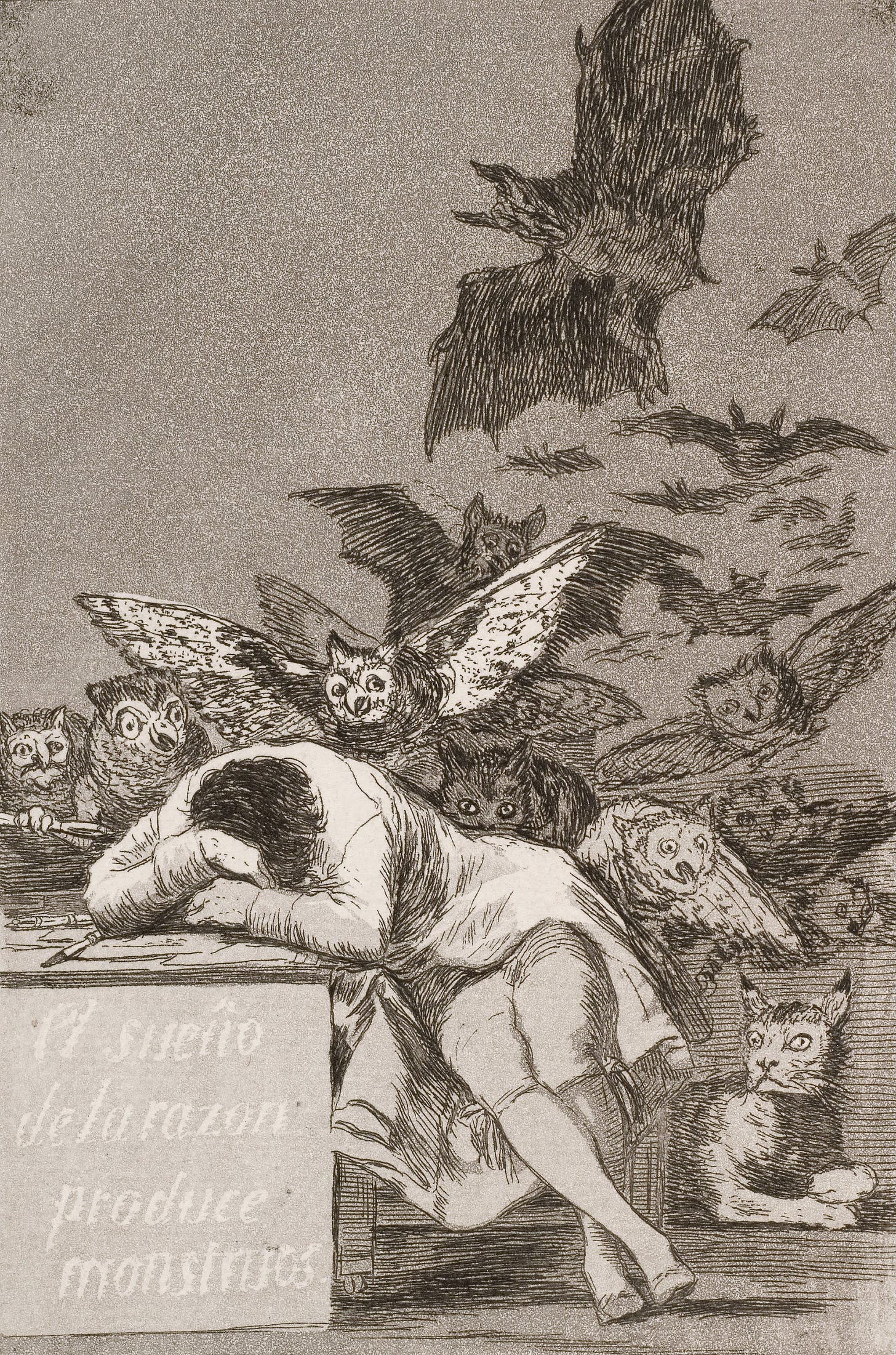

As I’ve tried to argue here, philosophical and psychoanalytic accounts of the subject have direct bearing on biography and biography, by extension, has a political valence insofar as it can reveal the objective conditions of our time, it aids us in more truly comprehending our present. The question for Marxism returns us to class, namely, can we turn to proletarian biography in such a way that we arrive at an objective understanding of our age? Any literature that is capable of driving us towards such a horizon, in a time when proletarian subjects are so deprived of use-time, would inevitably offer a direction for a political conception of social reality. In a time deprived of reality, biography is not our final answer or prescription, it is merely that which needs to fly at dusk but only after its suppressed truths have been revealed.

On Sartre’s relation to psychoanalysis and his Flaubert study I would recommend that you listen to my interview with Mary L. Edwards.

See Thomas Teo, “Klaus Holzkamp and the Rise and Decline of German Critical Psychology” History of Psychology, 1998, Vol. I, No. 3, 325—253.

Roche, Julian “Can Biography Benefit from a Marxist Theory of Individuality? Lucien Sève’s Contribution to Biographical Theory and Practice” Rethinking Marxism, Vol. 30, No. 2, 291—306.

Read Jameson’s review of Sartre’s The Family Idiot in the New York Times back in the 1980s.

See Notes to Literature by Theodor W. Adorno, p. 140.

The dialectic of use-time and abstract-time has many points in common with the ongoing and elaborate—at times brilliant—work of TIMENERGY: Why You Have No Time or Energy by David J. McKerracher.