I’m pleased to share an essay on the Althusserian theory of ideology that will be published in a forthcoming issue of "Logos" a leading Russian philosophy journal. This paper was first offered as a talk for the READING ALTHUSSER conference organized by Lacan Link. In this essay, I examine the role that Lacan’s concept of the imaginary plays in the development of the wider theory of ideological interpellation for Althusser. What remains ambiguous in this legacy of ideology critique, for all of its descriptive richness, is a practical problem for collective politics: how do subjects “talk back” to interpellations such that they avoid getting entangled in further ideological misrecognition? This introduces us to an entirely new level of ideology critique, what Engels theorizes as ideology as “counter power”, or the means by which subjects organize “disidentifications” to “counter identifications” that can rival bourgeois power.

This theory of counter power introduces us to a dialectical dimension of ideology critique. It requires the appropriation of both scientific concepts and identifications with political organization of a new type. Without this institutional dimension and attention to political organization, ideology critique will tend to remain ensnared in an individualist pessimist perspective in which political activity is theorized as caught in inevitable, if not eternal, phantasmatic capture. To unravel the dialectical core to this constructive domain of ideology critique, I turn to the work of the lesser-known philosopher and linguist Michel Pêcheux—a student of Althusser—who maintained that the task of socialist organization requires the creation of a “counter identification” to overcome the capture of dominant ideological interpellations of the working class.

It is this move from primary “disidentification” to “counter identification” that I find missing in the work of ideology critique in Slavoj Žižek and many post-Althusserians. For Žižek, the wider process of counter-identification is thrown into question as inevitably entailing a further imaginary subjection, and this pessimist move leads him to abandon the politics of identification entirely. My argument is that without a constructive theory of counter power and counter-identification, ideology critique will inevitably fall sway to pessimistic idealism and this results in a passive theory of ideology that cannot effectively theorize how collective liberation from ideology is overcome.

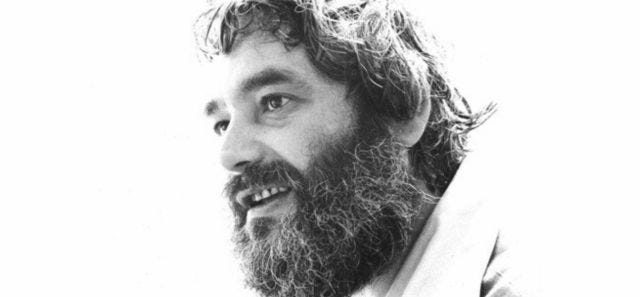

Althusser has been a constant source of philosophical reflection and an important point of reference for my work lately. I have hosted study groups on For Marx Althusser’s important study of the early Marx and The Political Unconscious by Fredric Jameson—a book which is deeply Althusserian. A video of my talk which is the basis of this essay can be found below.

Psychoanalysis and the Althusserian Theory of Ideology

The Althusserian theory of ideology underwent successive re-workings that correspond to Althusser’s continual intervention in the political context. Initially, the theory of ideology designates the opposite of science, before it is thought as an element of the social formation, which is represented in his mature work on the topic, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses from 1970. We get a deeper sense of Althusser’s view on ideology in a letter from 1964 to his lover Franca Madonia, where he describes ideology with a metaphor, from which “Marx, but also Freud, Nietzsche, and Spinoza have managed to liberate themselves”, they have succeeded he writes, “in lifting this enormous layer, this tombstone that covers the real.”1 This is reflected in his earlier work For Marx where Althusser theorizes ideology not as a concept reliant on a theory of consciousness but as an ideological unconsciousness that men have towards society. The concept of ideology is thought in relation to the concept of the “problematic” and as such, knowledge of the ideological field presupposes knowledge of the problematic that is compounded or proposed in it.2 Ideological forms are unified by a problematic, from religion, ethics, legal to political ideologies, and these domains are sites of ideological investment, or imaginary representations of real conditions of social existence.

Althusser places the theory of ideology on the political terrain in such a way that ideology is deployed to think the conditions of specific struggles, but a clearly defined transformative political perspective is not fully developed. What is emphasized in Althusser’s theory of ideology is the importance of superstructures and the relative autonomy of the struggles that unfold within them. In the wake of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and May 1968, Althusser reinvents the theory of ideology in his famous essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” such that ideology is thought as a structured formation, no longer as a set of illusions, or what could not be scientifically formalized. The essay, published in 1970, takes on the function of reproduction: law, religion, school, family, etc. and argues that all levels are uniquely politicized. This results in a conception of class struggle that is effectively geared towards an array of non-totalizable specific struggles. The most useful tool that Althusser’s theory of ideology develops in this essay is the notion that revolutions can occur in a 'weak sense', i.e., some revolutions only affect the ideological state apparatus without managing to transform the relations of production and thus the power of the state.

Althusser points to these weak revolutions as having occurred in 1830 and 1848—and one can infer—in 1968. The unique dynamics that spawned the Chinese Cultural Revolution were driven by a much wider durability of ideological forms that persist even in the face of a revolution in the economic base of society. It is the ideological question, now politicized as what Althusser refers to as “theoretical practice” that remains the primary terrain of political struggle, “the only theory able to raise, if not to pose, the essential question of the status of these disciplines, to criticize ideology in all its guises, including the disguises of technical practice as sciences, is the theory of theoretical practice.”3

What must be avoided in Althusser’s conception of ideology is the imposing of an interiority onto the idea, this after all is Hegel’s grave error in his conception of the dialectic. Hegel cannot think social conditions because he begins with a simple original unity that develops within itself by virtue of its negativity and throughout its development this original unity is only ever restored to its original simplicity in a concrete totality.4 This interiority of the idea is a sticky point that ties the Hegelian philosophy to what Althusser calls an “expressive causality” in which ultimately what is expressed in the interiority of the idea is an expression of the bourgeois ideological forms of the philosopher’s time. In For Marx, Althusser argues that “conditions do not exist for Hegel” and the movement of the Idea cannot overcome its own interiority.5

But is Althusser not guilty of the same error that Hegel makes in his theory of ideology as the subject’s imaginary representation to his or her real conditions of existence?6 Althusser leaves Marxism without a well-defined aim of radical transformation of the economic and social formation and without a fleshed-out theory of how subjectivity contests ideological interpellation. The theory of ideology in Althusser is reliant on a particular conception of the Lacanian category of the imaginary that limits any capacity to theorize how subjective interpellation is overcome and the adoption of Lacan threatens to undermine Althusser’s original criticism of Hegel that we addressed above, namely the following problem emerges: it is unclear whether Althusser’s theory of ideology—and indeed the wider enterprise of ideology critique that Althusserianism gives rise to—remains mired in a fatalist subjectivism in which ideological predicaments and subjection to ideology is ultimately untranscendable.

The problem of the overcoming of ideological capture and subjection is of course, at least in theory, already accounted for in Althusser’s negation of the ideological by ‘science.’ The science of history is reliant on a theory of discourse that understands the subject in relation to ‘objective’ processes of production and social formation that do not adequately account for the subject’s standpoint in human praxis. Or put differently, the subject is thought within the matrix of class antagonistic forces in social life. Lacan’s conception of the imaginary, however, adds a different understanding of the subject and of subjection that Althusser understands as prior to class struggle. Lacan and psychoanalysis more generally contribute to a metaphysical account of the subject which cannot think contradiction. In a letter to Lacan written on December 10th, 1963, Althusser writes:

“One can always escape the financial and social effects of a social revolution…[But] I am speaking of a different revolution, the one you are preparing without [your adversaries] knowing it, one from which no sea in the world will ever be able to protect them, and no respectability, whether capitalist or socialist, the one that will deprive them of the security of their Imaginary…”7

Lacan’s lesson to Althusser is subjective, but it is singular and compelling in that it aims to address what is ultimately an unfinished problem for Marxism, namely: the theory of alienation. If the Lacanian theory of the subject results in a fatalistic conception of alienation, this might help to explain Althusser’s wider pessimism regarding alienation that he developed in For Marx. Althusser never develops an account for how the practical negation of the condition of alienation among the proletariat is posited as solved by philosophy in the young Marx. In Rancière’s view, the problem of subjection that Lacan develops leads to a distortion that fundamentally compromises the practical development of Marxist practice and its scientific status, such that Lacan contributes to ‘setting Marx free from Marxism’ in Althusser.

“Subversion had to find another path and, strangely, this path turned out to be the autonomy of theory. Reading Capital grounds this autonomy on the thesis that agents of production are necessarily deluded. By agents of production, we are to understand proletarians and capitalists, since both are simply the agents of capitalist relations of production and both are mystified by the illusions produced by their practices. Put bluntly, the thesis that grounds the autonomy of theory is this: false ideas originate in social practices. Science, conversely, must be founded on a point extrinsic to the illusions of practice.”8

Science now emerges as a point intrinsic to practice, namely as the real, and this results in what is effectively a two-level conception of the subject along an imaginary-real axis. It also results in the development of an entirely new domain of ideology-in-general which deepens the overall problem of subjection.

Althusser, Psychoanalysis and the Vicissitudes of Ideology-in-General

It is well-know that Althusser conceives of ideology in a broadly Spinozist manner: the imaginary is the name of the phantasmatic relation that men maintain with their conditions of existence, but within this relation no rational clarity is immediately possible. Imaginary subjection is like a stain on the subject that shapes how they relate to their social conditions – this prior mode of subjection is what we will call ideology in general. The reason for this stain is situated on the side of the reality of social relations themselves, and thus any direct causal relationship between the real and its representation is abandoned in favor of a homology of structuration that occurs on both sides of the imaginary and the real. Any exit from ideology proves impossible because there is a fundamental rupture that divides theory from the real.

While it was Althusser’s exposure to psychoanalysis, both Freud and Lacan, that led to the formulation of the notion of ideology in general the incorporation of psychoanalysis into Althusser’s wider oeuvre was colored by a climate of hesitation to incorporate psychoanalysis within the French Communist Party (PCF) due to the lingering view, largely informed by Stalinist anti-intellectualism, that psychoanalysis is ultimately a bourgeois science. The correspondence between Althusser and Lacan and the “Tiblisi Affair” both attest to this climate of repression and even censorship that forced Althusser to harbor his incorporation of psychoanalysis in at a distance.9 This case shows that Althusser faced ridicule, derision and even censorship from the communist movement for his wider view that “Freud has the advantage over Marx in thinking dialectics” and that “his thought is at times richer than Marx.”10

My talk with Lacan Link:

Althusser defends the scientific basis of psychoanalysis against the famous French Marxist philosopher Georges Politzer in an article from 1964-1965 entitled “Freud and Lacan.” In this article, Althusser reads psychoanalysis as possessing “authentic scientific concepts” and he reads Freud as a materialist for two primary reasons: First, Freud rejects the primacy of consciousness and this makes psychoanalysis opposed to all forms of idealisms, from spiritualism to religion etc. Second, Freud’s view that “the unconscious does not know contradiction” offers an entirely new way to theorize contradictions wherein the absence of contradiction becomes the condition of contradiction and the basis by which contradiction is not over-determined. The theory of unconscious contributes to an understanding of the subject that is “without history and eternal”, to what Althusser refers to as “omnipresent, trans-historical and therefore immutable in form.”11 This theory of the unconscious leads to a conception of ideology in which