Death and the Social

The Social Question in the Twenty-First Century

When my stepmother died it rained during her funeral. This was highly unexpected as California was in the middle of a three-year drought and there was no rain in the forecast that afternoon. As far as I can tell, this was a total weather anomaly. She was the sort of person that would have seen the rain as a spiritual sign, and likely as a good omen. And we celebrated it as such. It was a difficult funeral because she died too young. Something didn’t feel right about the whole thing, not necessarily because of the specific dynamics and events that led to her death but because I began to see her death as part of a far wider social breakdown. Once you experience half a dozen people that die too young, too unexpectedly and too untimely, the social dimension of their deaths start to come into focus.

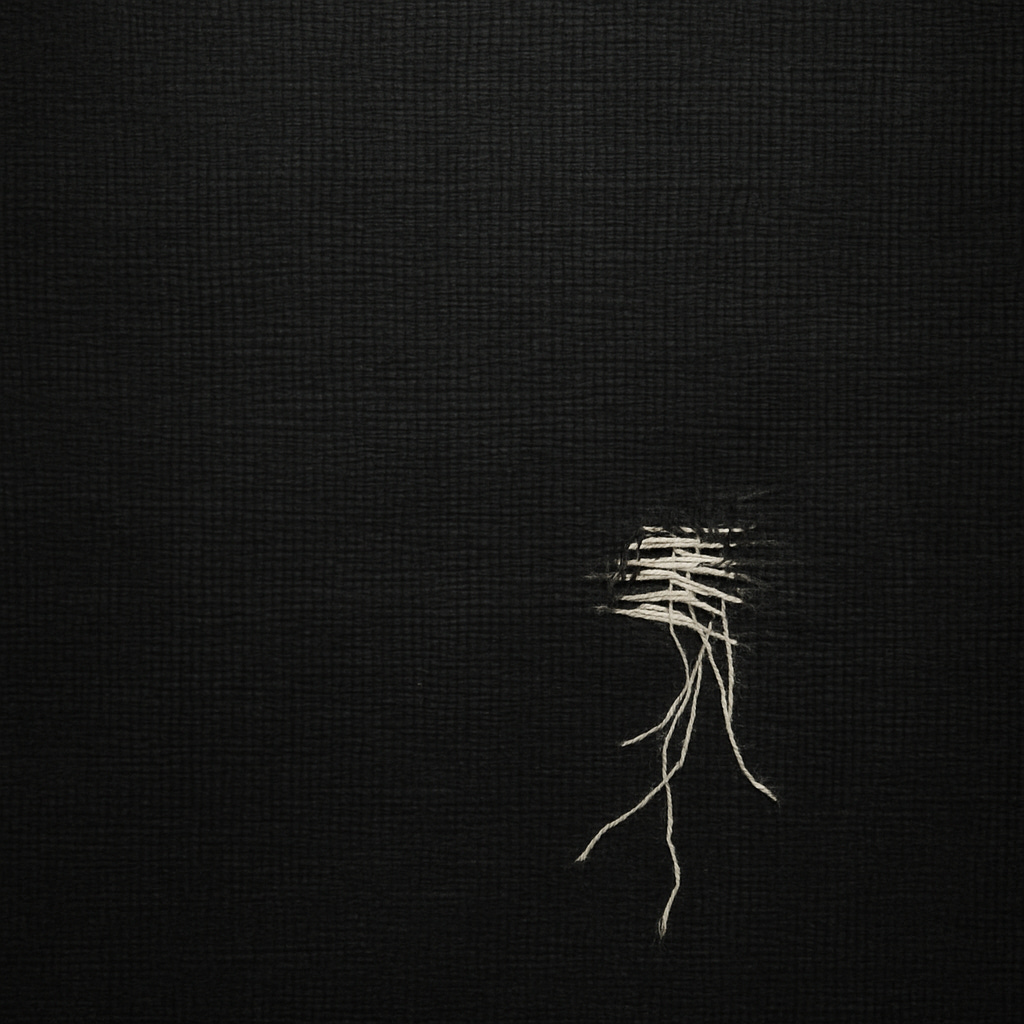

The thing about social deterioration is that it is not understood as a social phenomenon to those most acutely affected by it. Nowhere is this more evident than in the deaths of despair. I’ve come to see these deaths of despair, or deaths from alcohol and drug overdoses and suicide up close. I want to get a few things off my chest about them. Those who are dying from these deaths of despair tend to lead lives that have a hidden dimension of struggle and toil. It is as if the social existence of their subjectivity has become invisible to others. We seem to have lost the basic common sense to link these deaths to something that is locatable in a common social cause. We don’t die social deaths anymore.

The deaths of despair are a class and economic phenomenon primarily but they are not reducible to that precisely because the immensity of these deaths produce a deeper spiritual, moral and cultural crisis. From 2015 - 2025 it is estimated that over 1.5 million people have died in America from drug and alcohol overdoses and suicide. Social scientists will tend to posit ‘multi-causal’ factors for what drives these deaths of despair, and they eschew ‘poverty’ as the primary cause. However, empirical studies have shown that income inequality and lower rates of social mobility are directly associated with higher death rates from suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related liver disease among workers. A 2025 study noted that although overdose deaths increased over 2000–2019 generally, counties with worsening economic distress saw especially large increases.

What is clear is that these deaths defy our capacity to adequately memorialize and thereby mourn those affected by them. Do we mourn these deaths when we see them as linked fundamentally to a far wider social nexus? How can we begin to equip people with the courage to begin to see these deaths as linked and related? Perhaps we fear that, in making these connections, that we somehow betray the singular individuality of those who have died? Perhaps by introducing the social to these deaths we complicate our collective capacity to properly mourn them?

As Marxists and socialists we should not reduce our analysis of this crisis to poverty alone. What we are facing is so immense, so overwhelming in its weight, that it calls upon us to re-open what in the history of our tradition is known as “the social question.”

The Social Question and Deaths of Despair

In W.E.B. DuBois’s biography of John Brown he points out that John Brown had lost nine children prematurely. DuBois suggests that this trauma only hardened Brown’s resolve to address the primary social question of his time, which was the persistence of slavery. The social question was at the heart of the class struggle throughout the 19th century. For the early socialists of the 1830s, the social question referred to the necessity to resolve the condition of the industrial proletariat by providing a completely new society. By the time of the 2nd International, the social question was—as Kautsky argues in The Class Struggle—the core of the revolutionary tradition. It pointed to the confluence of social misery that capitalism had brought about in the lives of the working class. But the social question was also the source of profound debate between reformists and revolutionaries, it pointed to what we might call an overdetermined set of contradictions that cannot be pinned down to one primary antagonism. The social question was at the heart of revolutionary socialism and no degree of reformism, charity or welfare could adequately resolve it.

The social question is fundamentally political. It cannot be solved by charity, moral improvement, worker cooperatives, or piecemeal reforms. The rise of neoliberalism has regressed to a form of social rule that resembles the Elizabethan Poor Laws, a more brutal method of post-welfare social control. In Gilles Châtelet’s To Live and Think Like Pigs we are given a sense that this new form of social control is akin to the philosophy of Joseph Townsend who wrote in his famous work Dissertation on the Poor Laws—an important 18th century blueprint for how to manage the poor’s suffering.

Townsend argued against the Poor Laws by declaring that the poor’s suffering increases in proportion to the aid provided to them, and thus in order to pacify the poor the ruling class is better served to avoid welfare. Townsend advocates that the poor rely on their own labour, family networks, and voluntary private charity, not on a legal entitlement to relief. Townsend argues that the state should protect property and contracts but not guarantee subsistence. In a way Townsend seems like he is skywriting the means-tested neoliberal post-welfare logic of today’s PMC who argue that welfare is only to go to those truly deserving, it should not be implemented as a standing right. As Townsend remarks:

“There never was greater distress among the poor: there never was more money collected for their relief. But what is most perplexing is that poverty and wretchedness have increased in exact proportion to the efforts which have been made for the comfortable subsistence of the poor...”

The long history of the worker’s movement shows that the social question is always already bound up with the political question. Marx would come to learn this firsthand. Early on in his career he saw that many socialists would advocate the social question by empowering liberal politicians to implement some social oil to alleviate extreme conditions. But this would never come to pass, the contradiction between labor and capital would rear its head again and again and send the class struggle into a downward spiral. Marx aimed to unify the social question with the political question, or the seizing of the state apparatus and power. He saw appeals to remediate the social ills through liberal methods as something akin to today’s talk of ‘social justice’ which is content to provide just a little bit of social lubricant into the gears and levers of society to pretend that we still have a society and to pretend that still operates.

A new 21st century social question will have to situate the deaths of despair at its very center. To do so will require that we muster the resolve and thereby the courage to shrug off all sentimentalist appeals to blind fate and individual chance and accident. It would require that we begin to see that capitalism has not only killed us off too early, we must see something worse, namely that capitalism has disrupted our very capacity to see how it is killing us. Such a vision would be set on restoring dignity to our shared social existence.

Wonderfully moving, and I mean that in both the individual and collective sense of the word: to be moved into political action. Thank you.

is it possible to place people who die as members of violent organized crime (such as gangs or cartels in Latin America) in this category of deaths of desspair? There are many statements from young people who know that they are entering a "job" where they will not live long, but who do so because they see no other opportunity in life. This sounds like a kind of suicide.